So are these low rates still just a temporary phenomenon till the economy gets going again? How much longer could temporary last? The answer is many years, it appears. Here's why.

Demographics will be a decades-long stiff headwind - The combination of increasing longevity exacerbated in the immediate future by a mass of retiring baby boomers (mea culpa, I'm one of them) means the working age population will continue falling for the next several decades (see graphs in the Globe and Mail's Boom, Bust and Economic Headaches of November 2015). It's happening not just in Canada but throughout most developed economies as shown in the chart below from the Bank of Canada report Is Slower Growth the New Normal in Advanced Economies?

(click image to enlarge)

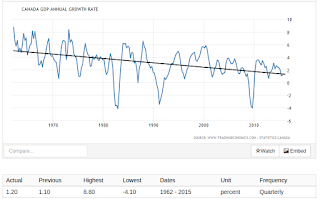

A growing population and a growing working population is a major source of economic growth so when it is slowing down, as it forecast to do, that is causing forecasts for economic growth to be constrained to lower than historical performance. Long term Canadian economic growth forecasts hover around 1.7% (TD Bank, Royal Bank and the Centre for the Studies of Living Standards and the Parliamentary Budget Office cited in a paper from the CD Howe Institute), or a bit higher 2% (OECD in an older 2013 forecast). That's a contrast to the heady years of the 1970s, 80s and 90s when 2% growth was considered a poor year. The downward trend is very evident in this chart from Trading Economics.

(click image to enlarge)

Sluggish growth means continuing low interest rates as central banks including the Bank of Canada attempt to provide policy stimulus. In slow growth there is less demand for money for investment to take advantage of business opportunities. Meantime, the greater mass of retirees buying bonds or pension funds and insurance companies offering annuities, i.e. supplying money for companies and governments to borrow, provides supply that also pressures rates lower.

Paying off massive accumulated government and private debt will also work to keep rates low - The huge amounts of debt that helped precipitate and exacerbate the 2008 financial crisis still have not been paid down to more normal sustainable levels according to common consensus (e.g. see the Bank of Canada paper cited above, also the US-based money manager Research Affiliates 3-D Hurricane's colour-coded map of countries' debt levels). McKinsey & Company reported in early 2015 that worldwide debt has increased, not decreased since the financial crisis. Canada may have started better off with significantly lower debt but it is worsening. One of McKinsey's charts (see below) shows Canada's total private and public debt rising much faster than the USA and the UK. It is hard to see that changing with a new federal government in Canada taking the stance that deficit spending to stimulate the economy is a priority.

(click image to enlarge)

The motivation of many countries to make their debt loads more sustainable will lead them to keep interest rates low, a policy caustically termed financial repression.

In October 2015, the CD Howe Institute published a paper by Craig Alexander and Steve Ambler that projected a 1% real interest rate on T-Bills for the long term based on expected economic growth, itself based on projected demographics. Adding 2% inflation, that would amount to a 3% nominal rate, which is about 2.5% above the slightly less than 0.5% as of the end of January 2016 (see Bank of Canada T-Bill rates). A 1% real rate is far below the 2.2% real T-Bill return achieved over the last half century according to the Credit Suisse Global Investment Returns Yearbook 2015.

1% real risk-free interest rates are most likely an upper bound. The Credit Suisse report says the real T-Bill return was only 0.4% from 2000 to 2014. When TD created its forecast in December 2015, it projected a 1.8% end of year nominal rate on 10-year Government of Canada bonds. But no sooner had it done so than the yield dropped to about 1.25% where it stands now. One wonders if TD would still stand by its forecast of a 10-year rate rise to 3.45% by the end of 2019. Leo Kolivakis at Pension Pulse even makes a case that negative interest rates might be around the corner in Canada and the USA in his observations following the Bank of Japan's recent cutting of rates below zero (i.e. charging banks to keep cash on deposit).

Bottom line: It seems within the realm of possibility that interest rates in Canada would rise the 1.2% or so over five years that we previously calculated would make it worthwhile for a 60 year old man to defer buying an annuity till age 65. But the more likely outcome is for much less a rise. The strong forces of demographics and debt seem to be pushing in hard against a rise and they are not going to get better anytime soon. Looks like interest rates will continue to stay very low or at best rise slightly and slowly.

Disclaimer: This post is my opinion only and should not be construed as investment advice. Readers should be aware that the above comparisons are not an investment recommendation. They rest on other sources, whose accuracy is not guaranteed and the article may not interpret such results correctly. Do your homework before making any decisions and consider consulting a professional advisor.

Copyright 2015 Jean Lespérance All Rights Reserved

No comments:

Post a Comment